Let’s recap my journey of using various AI tools in a real customer project. The project was going for two years and focused primarily on modernization. What started as legacy hell, is now more maintainable. Deployments are more frequent and the customer gained more confidence developing new features.

The journey is split into three waves of AI usage and the last six months represent the last, third wave, which changed the way I work completely.

State of the project Link to heading

The codebase was a masterclass in everything that can go wrong over time:

- Architectural nightmare

- No modularity

- Unstructured data with cross-dependencies

- Unstructured messaging

- Lots of code duplication

- Unreadable code

- Very long functions

- Lots of Angular and Node.js anti-patterns

- Performance problems in critical business logic

- Initial devs not around for questions

This was by far the most challenging modernization project in my career so far. And I loved it! We dealt with hard problems, nasty bugs, tough decisions, and of course deadlines. We used several patterns to move into a modernized world:

- Strangler Fig to migrate legacy modules

- CDC to synchronize real-time data

- Dual Write to move towards a more robust data ingestion pipeline

First wave - ChatGPT Link to heading

With all the to-dos we had to deal with and deadlines creeping up, I needed answers for questions quickly. I started using GPT-4. It didn’t help me write code, but it helped me as a sparring partner when ideating. I basically replaced my Google searches with it. I was faster when analyzing error logs, when I had to understand tools that I never used before, when I had to understand small pieces of legacy code, or when I wanted to double-check architectural decisions before presenting them to the whole team.

Some of my first prompts looked like this

how do I fix this mysql error on docker: “[ERROR] InnoDB: The innodb_system data file ‘ibdata1’ must be writable”

Was I more productive? Definitely, yes! Not by a large amount to be fair, but I got answers instantly for my specific problems. Even results that maybe didn’t answer my questions directly, narrowed down the research space, which enabled me to find the answers that I was looking for after iterating a couple of times.

Code completions with Copilot was also a thing around that time, but I hated it. The code suggestions were just awful, especially in our brownfield setup. So nothing happened on that front for me.

I used ChatGPT until the o4 models every now and then. It was a good Q&A experience. The drawbacks were obvious though. It has no real knowledge about your project. You can’t just copy and paste your entire project into it and I needed a tool that actually “lives inside your project”.

This wave was the beginning. Tools like ChatGPT were useful. Google had to respond swiftly due to it and they released the “AI Overviews” feature in Google Search mid 2024.

Second wave - chat-based programming Link to heading

The next wave of AI tools emerged: chat-based programming. Copilot Chat, Cursor, Windsurf, you name it. It was an improvement over ChatGPT. You could now provide project context directly in your IDE, and the models had actual reasoning capabilities.

Models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet emerged with a strong emphasis on coding. Andrej Karpathy coined the term “vibe coding” and suddenly a hype train started rolling. Everyone seemed excited about this new way of building software.

But I couldn’t understand the hype. On brownfield setups like ours, the results were subpar. It worked okay for small tasks or chores you could automate, like generating boilerplate, writing tests for isolated functions, or scaffolding simple components. But for medium to large tasks? Not good. Lots of hallucinations, verbose code, and suggestions that ignored the existing architecture entirely.

Maybe it worked well for greenfield projects or simpler codebases. But for complex, especially brownfield projects with years of accumulated technical debt? No chance. The tools simply couldn’t grasp the intricate dependencies, the implicit conventions, or the “why” behind certain design decisions that only lived in the heads of developers long gone.

In general, I was still more productive with this new wave. I used a combination of ChatGPT for research and Copilot with Claude models for small tasks. I was implementing most of the work manually regardless. I was faster that way, and the tools simply weren’t mature enough yet to handle this level of complexity.

Third wave - coding agents Link to heading

In comes the third wave. Coding agents. Specifically, Claude Code. The first time I noticed Claude Code was when they released their introduction video on YouTube in late February 2025. In my skepticism, I watched the video, thought “cool another Copilot but for the terminal” and waved it off. I didn’t understand the potential and the design philosophy behind it at that time.

Months after, my esteemed colleague Marius Wichtner was going ham with Claude Code. He understood early on the potential of parallel agents and hacked on para which evolved into Schaltwerk. Around that time, MaibornWolff was going through an AI transformation and Marius was one of the main drivers trying to spread his knowledge.

Marius was explaining how his whole workflow changed from the ground up and I just had to know what he was doing differently to gain so much productivity with Claude Code. I pinged him, we talked the same day after work, and he explained to me in detail how he works. After being mind-blown, he encouraged me to watch the talk from Boris Cherny, explaining Claude Code in 30 minutes and some agentic coding best practices. Lastly, he said to just try it out in order to develop an intuition and that was probably his best advice.

After successfully pitching Claude Code to the customer, I was very excited to try it out in a real world scenario. The models around that time were Sonnet/Opus 4.

What followed were six months of completely redefining how I work. The integration was seamless, each model upgrade brought noticeable improvements, and I found myself rarely coding manually anymore. Here’s what we did along the way.

Claude setup Link to heading

Every project should start by defining one or more instruction files. Every repository had at least one CLAUDE.md file in the root of the project. Our monorepo, representing modernized microservices, leveraged nested CLAUDE.md files. This way we provide enough context upfront for each task.

monorepo/

├── CLAUDE.md

├── apps/

│ ├── service-a/

│ │ └── CLAUDE.md

│ ├── service-b/

│ │ └── CLAUDE.md

│ └── service-c/

│ └── CLAUDE.md

└── libs/

├── shared-utils/

│ └── CLAUDE.md

└── common-types/

└── CLAUDE.md

The files at the root level describe the project. Tech stack, project structure, project purpose and how to work in the project. Legacy repositories also define their nuances, so that the agent knows how to behave there. Nested files describe the respective microservice or shared utility. Try to keep these files as small as possible to get the most out of your context window. Our root files were roughly 100 lines long and we tried to not exceed more than 300 lines. Nested files were mostly around 50 lines long, at most 100 lines.

That was the only setup we had the entire time! We didn’t have shared custom slash commands, skills or custom subagents. Some colleagues utilized them individually by defining it on the user-level, but most of our output came from good planning, prompting and rigorous reviews.

Workflow Link to heading

Research Link to heading

I was leading a subteam in the project so I had two modes of working. Either fixing high priority issues to unblock us (more about that below) or architecting the next migration/feature. Either way, I would always start with research. Where are we right now? Where do we want to go? How do we reach our goal in the most pragmatic way? I prefer simple solutions. They are easy to understand and easy to maintain, which is why I wouldn’t mind spending some extra time to find a simple solution.

The whole ideation and ping-ponging that I would usually do with ChatGPT, moved entirely into Claude Code. Suddenly the research space was filled with way more qualitative results and the difference was noticeable, and it makes sense. The agent has an understanding about the architecture, it can traverse your project to find more information, it understands images and can do web search.

I would first come up with an idea myself, get feedback and look for alternatives or best practices with the agent, and then iterate until I was happy with the solution. Comparing how we started in the beginning with no AI and the early ChatGPT era, I noticed that research took us now minutes instead of hours. Some of it can be probably accounted towards the overall project being in a better state than it was in the very beginning, but we still had to deal with non-trivial migration topics and feature requests, and if I compare doing research for the same kind of task pre and post Claude Code side by side, then Claude Code wins for sure.

Implementation Link to heading

When it comes to implementing stories, I started with the integrated plan mode. You see what the agent wants to do, you review it, and adjust it if needed. It worked well and got better with every new Claude Code update. Later, I would create plan files to enforce the agent working with a todo list system and nowadays I use frequent-intentional-compaction to get the most out of my context window.

Agent output is heavily reliant on good prompts. Shit in = shit out. It’s as simple as that. My rule of thumb is mostly:

- Be as detailed as needed for the task

- Explain the purpose (helps reasoning)

- Provide examples (logs, images, a similar solution, …)

I regularly see people on social media complaining about poor agent output, but when you read their prompts, the problem becomes obvious. Somehow they expect quality results from zero context and vague instructions…

Parallel agents Link to heading

I tried using parallel agents once as an experiment to complete an epic quickly and to get a feeling for it. The epic was a perfect candidate for the experiment, since we completed another epic before that was similar.

Although I could have used Git worktrees, I decided to run multiple agents on a single feature branch, because why not. So I did some well-curated task slicing in order to eliminate conflicts and ran three agents in parallel. One for the backend, another one for one part of the frontend and the last one for a different part of the frontend.

The results were good. I expected nothing else to be honest. The only thing I learned is that you have to focus really hard managing multiple agents. Ultimately, I prefer to use at most two agents. It’s a sweet spot for me balancing focused work and a parallel workstream. With one I do my main work and monitor the progress and with the other I check things in between.

I will definitely try out running more agents again, when I find the right setting and good UX for orchestration.

Human in the loop Link to heading

In my opinion, a non-negotiable for any serious (brownfield) project. Every output from an agent needs to be reviewed. Otherwise, you’ll end up in spaghetti real quick. With all the guardrails we define, agents can still drift at any step of your workflow and you want to catch that as early as possible.

I always review

- every plan file

- the agent’s steps while it’s running (depends on task complexity)

- the agent’s output

Before creating a PR, I review the code myself one last time and have another agent review it against my quality criteria. Once the PR is created, our Copilot agent does another round of review, and the final review and approval is done by a colleague.

Managing context matters Link to heading

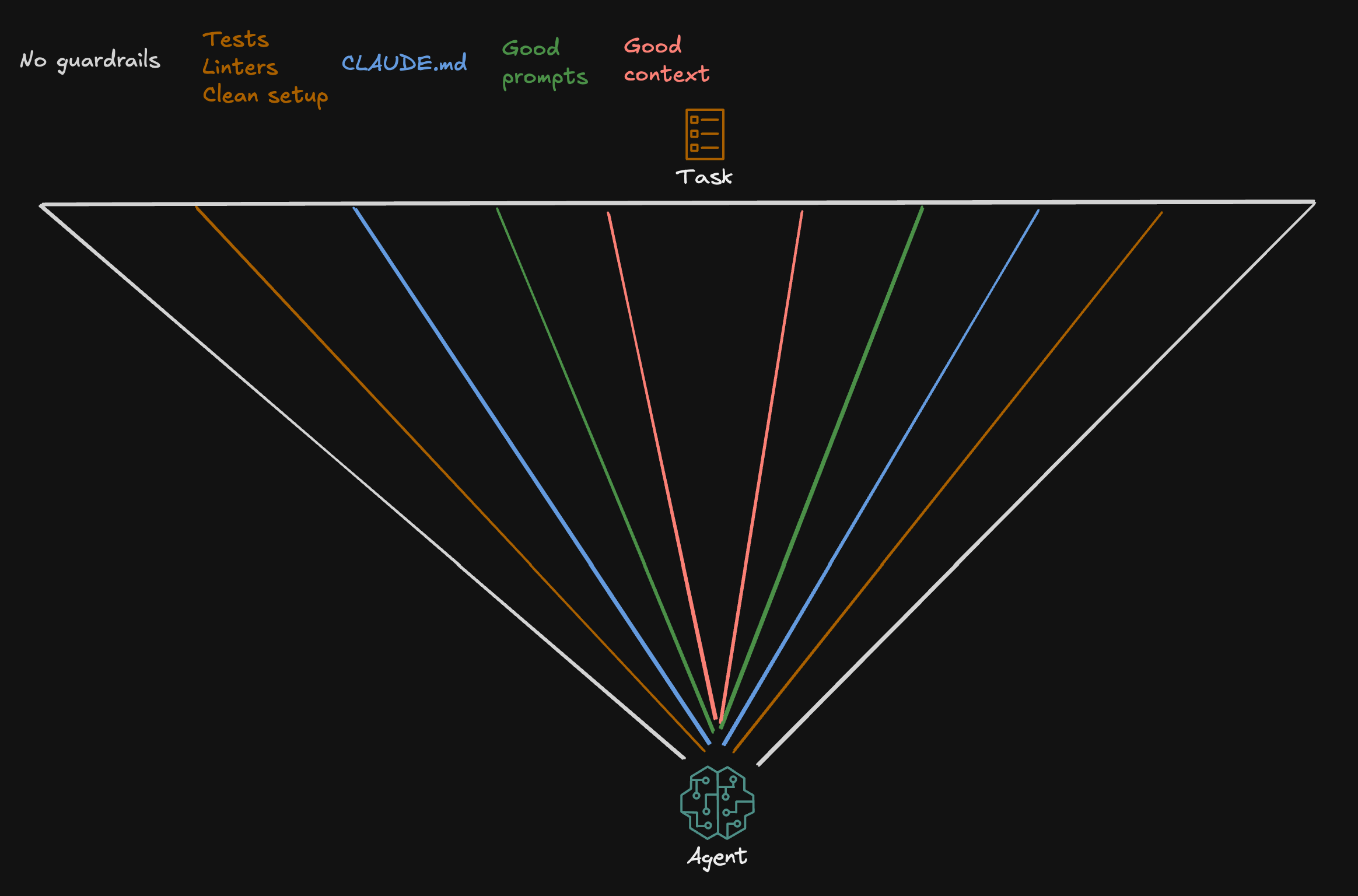

Currently, context management is what matters the most. People invest significant time in context engineering because it directly influences agent performance. Polluted context distracts the LLM and degrades the result accuracy. We want to provide the right information that is needed to fulfill the task as good as possible. But why are we doing this? My mental model of it is the picture below

Think of this as an agent aiming at a task from the bottom. The triangular area represents the room for error, all the possible ways the agent might interpret and execute your request. Without guardrails, this cone is wide, and the agent might land anywhere, making it unlikely to hit the target precisely. With each guardrail we add, we narrow the cone. The narrower the cone, the more laser-focused the agent becomes, and the higher the probability of one-shotting tasks.

Disabling auto-compact Link to heading

One of the first things everyone should do if they care about their context window size, is to disable auto-compacting. It is enabled by default and the auto-compact buffer pre-allocates space in your context window. So visit /config and enjoy the extra space. Auto-compact summarizes your conversation when your context window is about get full. The problem is that the summary can be lossy which can lead to polluted context in the next session, degrading the result quality over time.

Using master-clone subagents Link to heading

Subagents are a very powerful tool for managing context, since they have their own context window. This way you can offload for example noisy tool results that you do not care about in your main context window.

In our project, I never found a scenario where I would benefit from a custom subagent. What I used heavily though is what Shrivu Shankar describes as “Master-Clone Agents”, where the main agent creates copies of itself. They work great for research and exploration where you only care about the final result in your main context window or when you are doing bulk edits. When I needed subagents, I prompted something like

… use subagents to …

Designing your workflow around context management Link to heading

The more you work in this agentic setup, the more you will start to think about how to fine-tune your own workflow to get good results. Over these six months, I read a lot of posts where people were showcasing their own agentic workflow. And there is a lot of noise in the internet currently. It’s hard to find mature and realistic takes. Some setups were super crazy and some were obsolete after models got smarter. The core design around each however revolved around getting the most out of your context window.

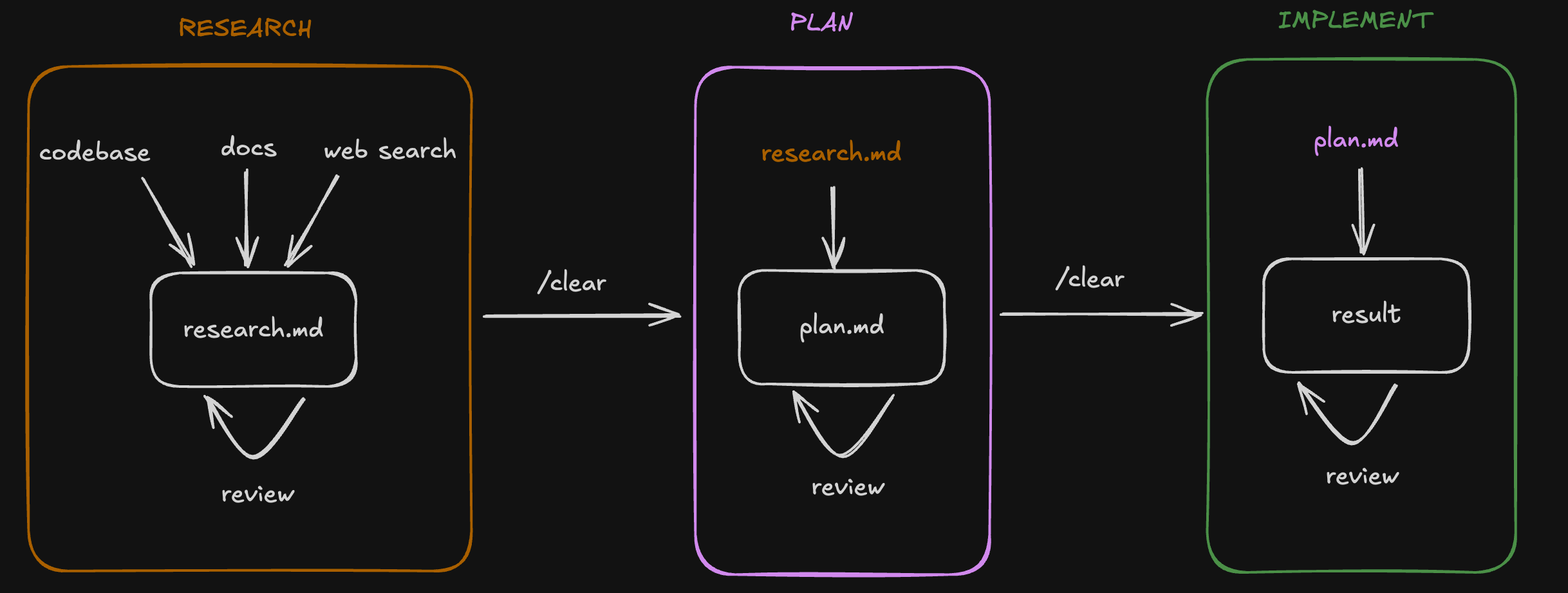

My workflow in the project was rather simple.

- Run a planning phase

- Review the plan and write it into file to treat it as external memory

/clearthe context- Implement the plan file and update its todo list along the way

- When context is about to be full (happened occasionally on large tasks)

- Capture the current session in a file

- Start a new session with cleared context and feed plan + session file

It worked well and I didn’t find the need to adjust my workflow. That changed when I watched Dex Horthy’s talk “No Vibes Allowed” on how to succeed in complex codebases utilizing what he calls “frequent-intentional-compaction”. At the same event, Jake Nations describes in his talk a similar approach, calling it “context compression” and how they succeeded with it refactoring their old authorization code at Netflix.

The whole concept revolves around RPI (Research, Plan, Implement). As described earlier, I had always done research before implementation, but it was informal. Knowledge that stayed in my head or in ChatGPT chats. RPI changed this by making research outputs explicit. Findings go into markdown files that become context for the agent. The research phase isn’t just for me anymore. It’s about building structured context that guides agent execution.

I had the chance to try this workflow together with Opus 4.5 in my last weeks of the project and it’s actually scary good. The model performance combined with providing structured context enabled me one-shotting some big stories.

Fixing bugs faster Link to heading

One of my first realizations when using Claude Code was how much faster we solved bugs. I dealt with lots of issues on every level of the system in these two years on the project. So I had a direct comparison how long it took me to solve issues before and after Claude Code.

- For backend issues, log analysis worked exceptionally well.

- For frontend issues, I would capture screenshots and explain reproduction steps.

- For complex issues, I would provide data, reasoning questions and narrow down the problem by tracking fix attempts on a file

The narrowing down approach was kind of interesting to me. We had a complicated frontend bug once where I had to resort to it, since I couldn’t get far with my regular fix workflow. I created a file with Claude to track each fix attempt. Claude wrote a fix, I tested the fix manually and reported back the results. On each failed attempt, Claude would update the file with my reported results and narrow down the problem further and come up with the next fix attempt. After a couple of iterations, the bug was found and fixed.

What surprised me was how rapidly I could cycle through that many fix attempts to find the solution. The whole process for this flow took at most an hour, if we add implementing tests for the fix on top.

To my surprise, Anthropic released months later a blog post describing the basic debugging flows.

Knowledge extraction from legacy world Link to heading

Working on legacy code has probably never been easier than it is now with agents. They reduce the time needed to understand business rules, dependencies, data flow etc. by a large amount. The Thoughtworks Technology Radar already recommends to seriously consider using GenAI to understand legacy codebases.

When we started to work on migrating the very first legacy module in the project, it took us roughly 1.5 weeks to understand and document everything. Remember the situation of the codebase? Unreadable code, long functions and everything? Yeah, we grinded through and read every piece of spaghetti code in order to extract knowledge. A necessary grind, but one that left you wondering if there had to be a better way.

Fast forward to a few months ago. The team was discussing the migration of another core legacy module. This time, I ran the initial spike differently. Instead of manually reading through every file, I let multiple agents do the research in parallel. Half a day later, I had a comprehensive understanding of the module, verified the findings together with PO’s, and was ready to design a migration strategy. By the end of the week, the first tickets were already created. What took us 1.5 weeks before, only for knowledge extraction, now took less than a day.

Understanding legacy data was another challenge entirely. In the same migration, we had to move MongoDB documents to Postgres in a well-structured manner. The problem? The legacy documents were polymorphic. They represented different entities based on the value of a single field, and even then, edge cases existed. We were dealing with roughly 80k documents. Finding all anomaly patterns manually by firing queries against MongoDB was not realistic. So instead, I prompted the agent to run a full analysis on my local database. It identified all the anomalies, surfaced the edge cases I would have never found on my own, and gave me what I needed to design mapping logic that handles every case when consuming CDC messages. What would have been maybe hours or days of tedious querying turned into a conversation with an agent.

The future Link to heading

The following are topics I am excited about, either relevant now or becoming more relevant in the near future. They are based on my own observations or from online sources I find credible.

Better agents Link to heading

The harness around the LLM is improving constantly. Every Claude Code update brings new capabilities that make agents more effective. Better planning modes, smarter context management, improved memory handling. The model itself is one thing. How you orchestrate it, how you feed it context, and how you constrain its actions matters just as much. I expect these harnesses to get significantly better over the next year, making agents more reliable and easier to work with in complex codebases.

Managing multiple agents is still not easy. You need to track their progress, coordinate their outputs, and make sure they don’t step on each other’s toes. Right now, this requires manual effort and constant context switching. But agentic IDEs are emerging that provide a proper platform for orchestration. Tools like Schaltwerk, Google Antigravity, and VS Code Agent Sessions are early examples of what this future may look like. I expect orchestration to become a first-class concern, making it easier to run, monitor, and coordinate multiple agents without losing your mind.

Trying out new workflows Link to heading

With some spare time between projects now, I want to push my personal workflow further. RPI has been working well, but I know there is more to explore. Custom subagents and slash commands are features I haven’t fully utilized yet. Now is the time to experiment and see how they can fit into my daily work. I also want to try out tools that others in the community have built. Beads from Steve Yegge and Claude-Flow from Reuven Cohen are on my list. Both take different approaches to agent orchestration and context management. I am curious to see what I can learn from them and whether they can improve my workflow.

Prototyping was never easier Link to heading

Vibe coding1 gets a lot of criticism, and rightfully so when applied in complex codebases. But for throwaway ideas? It is perfect. You can test the potential of an idea in no time without investing hours into something that might not work out. This also opens doors for citizen developers who want to prototype product ideas without deep technical expertise. They can now bring concepts to life and validate them before involving engineering teams. At MaibornWolff, we ran a hackathon in our Agentic Modernization guild where colleagues got their hands dirty with Claude Code. The goal was to learn and develop an intuition for agentic workflows. The results were impressive. People with varying levels of experience built working prototypes within hours. Our unit head Claas Busemann wrote about it.

Software modernization efforts Link to heading

I already described how well agents work for legacy modernization based on my own experience. Thoughtworks also added this technique to their technology radar, validating that this is real and not a trend. Friends of mine are already exploring this within their companies. It is the classic situation. Someone is retiring, and decades of knowledge are about to walk out the door. They need to extract that legacy knowledge before they can even think about modernization. Agents are a perfect fit for this problem. Morgan Stanley has been tackling similar challenges. Anthropic published a video demonstrating a modernization example for a COBOL codebase. The industry is waking up to the fact that agents can help preserve and transform legacy systems at a scale that was not realistic before.

Pushing AI adoption Link to heading

AI adoption remains one of the current challenges for organizations. According to McKinsey’s research and their state of AI report, the gap between companies that benefit from AI and those that struggle is widening. The differentiator is not just adopting the tools. Companies that actively overhaul their processes and redefine roles around AI are the ones seeing real returns. Simply adding AI to existing workflows does not cut it. You need to rethink how work gets done. This will be one of the main questions organizations face in the coming years. Those who treat AI as a transformation rather than an add-on will pull ahead.

Unleashing agents beyond code Link to heading

Agents are not limited to software engineering. The same principles that make them effective for code work just as well in other domains. I use Claude Code to organize my Obsidian notes, clean up structures, and resurface connections I would have missed otherwise. When Anthropic started pushing Claude for financial services, I got curious. Together with my dear friend Max Weiss, who works as a finance manager, we tested some workflows from his day to day job. The results were promising. Tasks that involved analyzing data, summarizing reports, or preparing documents worked really well. There are surely many more use cases out there waiting to be discovered. Once you develop an intuition for working with agents, you start seeing opportunities everywhere.

Closing thoughts Link to heading

A year ago, I was skeptical about AI. Now I rarely code manually.

AI changed how I approach problems. It does not replace thinking, it amplifies it. For brownfield projects especially, this matters. Legacy codebases don’t need more vibe coding. They need careful extraction, deliberate modernization, and constant human oversight. Agents excel at exactly this when you set them up right.

The tools will keep improving. The real question is whether you’ll redesign your workflow around them, or just bolt them onto what you already do.

To me, vibe coding means minimal to no oversight. So no human in the loop. ↩︎